Greetings Fellow Parasitophiles!

I wanted to share with you, in case you hadn't already heard, that it has just been announced that there will be a new temporary exhibit that focuses on parasitism opening this April. The exhibit is called Guts & Glory: A Parasite Story. It opens on Saturday, April 22nd, 2017.

The exhibit explores the complex relationships that exists between hosts and parasites. It also traces the history of the field of parasitology and is sure to be phenomenal. Here is the Facebook page if you want to keep up to date about the exhibit: Guts & Glory: A Parasite Story

Further details about how long the exhibit will run are to be coming soon, so stay tuned!

Also, be sure to check out the H.W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology's website here if you haven't already.

I hope that those of you in Lincoln, Nebraska, will take the time to check this out and that those of you from out of town will consider making a road trip this way in April!

Sunday, February 12, 2017

Thursday, January 12, 2017

Cochliomyia hominivorax: Getting Screwed by Screwworms

Greetings at long last, fellow Parasitophiles! As you may have noticed, I haven't been able to post lately. I was busy finishing up my degree, graduating, and applying for more jobs than I can count on both hands. Time flies while you're having fun!

Speaking of flies...today, I wanted to talk with you about one that is particularly important given its current status. Have you ever heard of Cochliomyia hominivorax? Better known as the New World primary screwworm, this little beastie is capable of causing huge problems. This week, the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) confirmed a case of canine myiasis (a stray dog infested with flies) caused by C. hominivorax near Homestead, Florida.

This is really, really, REALLY bad news.

Why? You ask. Because we aren't talking about a fly that comes to feces or dead things to feast and lay its eggs. We are talking about a fly that prefers instead to dine on living host tissues that provide a nice, warm, plentiful food resource for its young'uns. Additionally, we are not talking about a fly that infests a few smaller mammals and lays an egg or a little clutch of eggs before flying off. No. Not with C. hominivorax. This fly has a wide range of documented hosts, including small mammals, deer, livestock, companion animals like dogs, and even humans. These unlucky hosts are not subject to small numbers of maggots when eggs hatch...an individual female C. hominivorax can lay up to 500 eggs at a time and during her lifetime, which lasts about 20 days from the time that she hatches from an egg, she may lay as many as 3,000 eggs! If you Google images of this organism, you are sure to find many disturbing pictures of cattle, dogs, humans, and other animals who suffered from these maggots. Particularly disturbing for me is finding photos of oral myiasis...that is, cases where maggots burrowed into the mouths of people. If you liked your lunch today and would rather not meet with it again, I'd advise you not to look that one up! For this post, I avoided such photos this time.

Why? You ask. Because we aren't talking about a fly that comes to feces or dead things to feast and lay its eggs. We are talking about a fly that prefers instead to dine on living host tissues that provide a nice, warm, plentiful food resource for its young'uns. Additionally, we are not talking about a fly that infests a few smaller mammals and lays an egg or a little clutch of eggs before flying off. No. Not with C. hominivorax. This fly has a wide range of documented hosts, including small mammals, deer, livestock, companion animals like dogs, and even humans. These unlucky hosts are not subject to small numbers of maggots when eggs hatch...an individual female C. hominivorax can lay up to 500 eggs at a time and during her lifetime, which lasts about 20 days from the time that she hatches from an egg, she may lay as many as 3,000 eggs! If you Google images of this organism, you are sure to find many disturbing pictures of cattle, dogs, humans, and other animals who suffered from these maggots. Particularly disturbing for me is finding photos of oral myiasis...that is, cases where maggots burrowed into the mouths of people. If you liked your lunch today and would rather not meet with it again, I'd advise you not to look that one up! For this post, I avoided such photos this time.

In short: These flies are baby-making machines with wings that need living, warm-blooded hosts to reproduce. This translates to some pretty serious issues for us, but before we go into the impacts that these creatures can have and have had in the past, let us look a little more closely at their biology.

Taxonomy

These flies, like all flies, are insects belonging in the order Diptera. They are placed within the family Calliphoridae with blow flies, like the shiny, metallic blue and greens that you often find buzzing around dead things. Five species are found within the genus Cochliomyia, including C. hominivorax. The epithet derives from words that loosely translate to "inclined to devour man".

Life Cycle

These flies live about 20 days when the weather is warm and may live a little bit longer in cooler climates. Adult females mate once in their lives before depositing between 250 and 500 eggs on the edges of open wounds or mucous membranes found on unlucky hosts. Three days to a week later, these eggs hatch and form maggot masses that burrow into the flesh of the host where the larvae feed on bodily fluids and living tissues. This causes wounds to enlarge as the screwworms feed, which in turn provides more places for other female flies to deposit their eggs. Left untreated, this infestation can be fatal to the host, which may be your pet cat, dog, or bird, your livestock animals (including cattle, pigs, goats, and sheep), things you hunt like deer or rabbits, or, in rare cases, even that uncle that you feel bad for laughing at when you realize how serious myiasis can be. (Don't worry, I'm sure Uncle Jack will seek medical treatment before it would kill him no matter how macho he tries to appear.)

After several days devouring Fluffy or Uncle Jack, the maggots will drop off of their host and burrow into the soil to pupate. This means that they form a hard shell known as a "pupa" and undergo a complex process before bursting out as adult flies. Do you remember that process from your basic biology courses? That's right! Metamorphosis...just like other insects, like butterflies, undergo to transition from little worms to winged beauties....except in this case beauty is relative (unless you are a male C. hominivorax). Anyway, good job reader!

After adult flies emerge from their pupae, they quickly mate and begin looking for a host with an owie for egg-layin'. These flies are about twice as big as your common housefly and feature three black stripes on their backs along with unmistakably orange eyes. They can travel several miles as adults, but are dispersed much further by their hosts as eggs and larvae.

Getting Screwed Since the 1920s

We have records going back to the 1920s of government-sponsored public education effort aimed at helping people to identify screwworms. A decade later, we were reporting cases of primary screwworms all across the south in the states and the USDA upped their extension efforts to teach people how to deal with them. In 1933, Emory C. Cushing within the USDA's Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine along with Walter S. Patton from the University of Liverpool in England published a paper describing the New World screwworm as a distinct species from the common blowfly, which many had mistaken as the same fly up until that point. Three years later, Cushing published a follow-up paper with E.W. Laake and H.E. Parish outlining the morphological and biological differences between the primary and secondary screwworms (C. macellaria). These were hugely important papers in the long and drawn-out battle between North America and C. hominivorax.

The 1940s saw the rise of the Third Reich and the slowing of screwworm research in the U.S. Many of the prominent screwworm scientists of the day were diverted to working with other organisms that troops would be dealing with in other countries during the second World War. Though domestic screwworm studies slowed, they didn't halt completely. Surveys continued with a disturbing report emerging in 1949 regarding severe infestations occurring in South Dakota on account of infected cattle being shipped into the state. This report by Raymond C. Bushland, the man who developed mass-rearing methods for screwworms by the late 1930s, highlighted the economic impacts of this fly and raised ranchers' concerns about the severity of these flies and how quickly they could be spread.

Edward F. Knipling built on Bushland's work by developing Sterile Insect Technique (SIT). This technique involves mass-rearing flies and then sterilizing them prior to release. Once released, the sterile flies mate with females, who typically only mate once in their lifetime, leaving them unable to reproduce. By the mid-1950s, several labs were experimenting and field testing SIT.

Glossing over a lot of really great stories about studies and struggles, we eventually found success with the implementation of large-scale SIT programs. Florida's eradication efforts led scientists to claim that the state, along with other parts of the Southeast, were screwworm-free by 1959. Seven years, billions of dollars, and a major partnership with Mexico later, the U.S. in whole was declared screwworm free. However, outbreaks continued through the 1970s and

the early 1980s. Since 1984, only isolated, imported cases have popped up, but otherwise North America has been pretty much screwworm-free. The 1990s saw continued efforts to push naturally-occurring screwworm populations south. Eventually, we got them eradicated as far south as Panama. You can read more details about this fascinating story here if you are interested.

Current Concerns

Which brings us up to current events. Over the last few months, we have seen new reports about cases of primary screwworm that have popped up along the Florida keys. Deer have been found to harbor these parasites, which were spreading quickly. With concern that the flies would make the jump to the mainland, eradication strategies were rapidly deployed on the islands. My entomologist friends and I have been tracking these stories in the news hoping to hear that the mainland was safe, but this week our fears were confirmed with the announcement of a stray dog having been found harboring C. hominivorax. The case spurred federal and state agencies to action and they are currently surveying the area to assess the extent of active screwworms in Florida.

For those worried, the stray dog was treated and is doing fine now that he isn't being eaten alive.

Aside from the obvious health concerns for people, wildlife, pets, and livestock, these flies could have catastrophic effects economically. Estimates from the USDA have reported that screwworm eradication has saved the U.S. livestock industry over $900 million dollars per year. Remember that this estimate doesn't include costs to pet-owners, breeders, or wildlife conservation efforts.

Here's to hoping that we can control whatever is already here and prevent future outbreaks, especially as if we see a long, warm spring/summer that would lead to a boom in any existing screwworm populations.

The Moral of the Story

The battle between us and the North American screwworm has been long and hard-fought. Countless man hours and dollars have gone into ensuring our victory over these winged beasties, and yet still they pop up from time to time because one person or another brought in an infected cow or doggy without considering the ramifications (or simply out of ignorance). This reinforces the importance of public outreach and extension efforts. Funding programs to continue educating the public about primary screwworms is both essential and inexpensive relative to the costs of dealing with established screwworm populations on a larger scale as was necessary in the past. Similarly, we need to be supportive of research in the control and prevention of parasitic insects.

Speaking of flies...today, I wanted to talk with you about one that is particularly important given its current status. Have you ever heard of Cochliomyia hominivorax? Better known as the New World primary screwworm, this little beastie is capable of causing huge problems. This week, the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) confirmed a case of canine myiasis (a stray dog infested with flies) caused by C. hominivorax near Homestead, Florida.

This is really, really, REALLY bad news.

Why? You ask. Because we aren't talking about a fly that comes to feces or dead things to feast and lay its eggs. We are talking about a fly that prefers instead to dine on living host tissues that provide a nice, warm, plentiful food resource for its young'uns. Additionally, we are not talking about a fly that infests a few smaller mammals and lays an egg or a little clutch of eggs before flying off. No. Not with C. hominivorax. This fly has a wide range of documented hosts, including small mammals, deer, livestock, companion animals like dogs, and even humans. These unlucky hosts are not subject to small numbers of maggots when eggs hatch...an individual female C. hominivorax can lay up to 500 eggs at a time and during her lifetime, which lasts about 20 days from the time that she hatches from an egg, she may lay as many as 3,000 eggs! If you Google images of this organism, you are sure to find many disturbing pictures of cattle, dogs, humans, and other animals who suffered from these maggots. Particularly disturbing for me is finding photos of oral myiasis...that is, cases where maggots burrowed into the mouths of people. If you liked your lunch today and would rather not meet with it again, I'd advise you not to look that one up! For this post, I avoided such photos this time.

Why? You ask. Because we aren't talking about a fly that comes to feces or dead things to feast and lay its eggs. We are talking about a fly that prefers instead to dine on living host tissues that provide a nice, warm, plentiful food resource for its young'uns. Additionally, we are not talking about a fly that infests a few smaller mammals and lays an egg or a little clutch of eggs before flying off. No. Not with C. hominivorax. This fly has a wide range of documented hosts, including small mammals, deer, livestock, companion animals like dogs, and even humans. These unlucky hosts are not subject to small numbers of maggots when eggs hatch...an individual female C. hominivorax can lay up to 500 eggs at a time and during her lifetime, which lasts about 20 days from the time that she hatches from an egg, she may lay as many as 3,000 eggs! If you Google images of this organism, you are sure to find many disturbing pictures of cattle, dogs, humans, and other animals who suffered from these maggots. Particularly disturbing for me is finding photos of oral myiasis...that is, cases where maggots burrowed into the mouths of people. If you liked your lunch today and would rather not meet with it again, I'd advise you not to look that one up! For this post, I avoided such photos this time.In short: These flies are baby-making machines with wings that need living, warm-blooded hosts to reproduce. This translates to some pretty serious issues for us, but before we go into the impacts that these creatures can have and have had in the past, let us look a little more closely at their biology.

.jpg/220px-Cochliomyia_hominivorax_(Coquerel,_1858).jpg) |

| Cochliomyia hominivorax adult. |

These flies, like all flies, are insects belonging in the order Diptera. They are placed within the family Calliphoridae with blow flies, like the shiny, metallic blue and greens that you often find buzzing around dead things. Five species are found within the genus Cochliomyia, including C. hominivorax. The epithet derives from words that loosely translate to "inclined to devour man".

Life Cycle

These flies live about 20 days when the weather is warm and may live a little bit longer in cooler climates. Adult females mate once in their lives before depositing between 250 and 500 eggs on the edges of open wounds or mucous membranes found on unlucky hosts. Three days to a week later, these eggs hatch and form maggot masses that burrow into the flesh of the host where the larvae feed on bodily fluids and living tissues. This causes wounds to enlarge as the screwworms feed, which in turn provides more places for other female flies to deposit their eggs. Left untreated, this infestation can be fatal to the host, which may be your pet cat, dog, or bird, your livestock animals (including cattle, pigs, goats, and sheep), things you hunt like deer or rabbits, or, in rare cases, even that uncle that you feel bad for laughing at when you realize how serious myiasis can be. (Don't worry, I'm sure Uncle Jack will seek medical treatment before it would kill him no matter how macho he tries to appear.)

After several days devouring Fluffy or Uncle Jack, the maggots will drop off of their host and burrow into the soil to pupate. This means that they form a hard shell known as a "pupa" and undergo a complex process before bursting out as adult flies. Do you remember that process from your basic biology courses? That's right! Metamorphosis...just like other insects, like butterflies, undergo to transition from little worms to winged beauties....except in this case beauty is relative (unless you are a male C. hominivorax). Anyway, good job reader!

After adult flies emerge from their pupae, they quickly mate and begin looking for a host with an owie for egg-layin'. These flies are about twice as big as your common housefly and feature three black stripes on their backs along with unmistakably orange eyes. They can travel several miles as adults, but are dispersed much further by their hosts as eggs and larvae.

Getting Screwed Since the 1920s

We have records going back to the 1920s of government-sponsored public education effort aimed at helping people to identify screwworms. A decade later, we were reporting cases of primary screwworms all across the south in the states and the USDA upped their extension efforts to teach people how to deal with them. In 1933, Emory C. Cushing within the USDA's Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine along with Walter S. Patton from the University of Liverpool in England published a paper describing the New World screwworm as a distinct species from the common blowfly, which many had mistaken as the same fly up until that point. Three years later, Cushing published a follow-up paper with E.W. Laake and H.E. Parish outlining the morphological and biological differences between the primary and secondary screwworms (C. macellaria). These were hugely important papers in the long and drawn-out battle between North America and C. hominivorax.

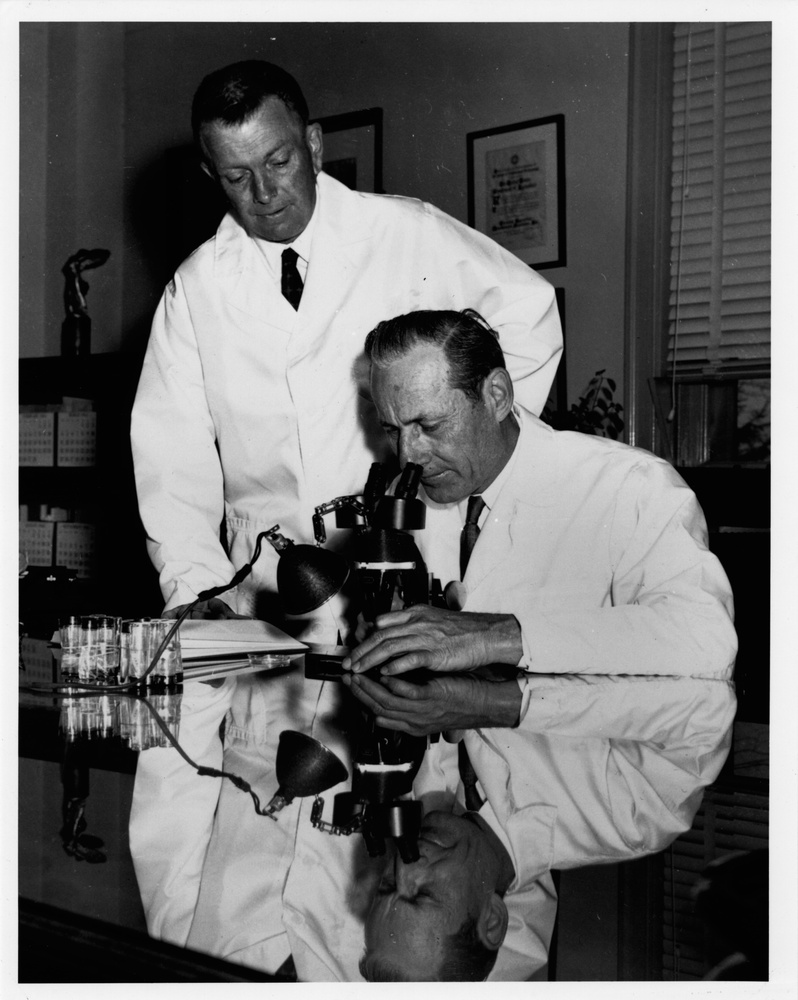

|

| Dr. Edward F. Knipling (seated) and Dr. Raymond C. Bushland. |

Edward F. Knipling built on Bushland's work by developing Sterile Insect Technique (SIT). This technique involves mass-rearing flies and then sterilizing them prior to release. Once released, the sterile flies mate with females, who typically only mate once in their lifetime, leaving them unable to reproduce. By the mid-1950s, several labs were experimenting and field testing SIT.

|

| Primary screwworm eradication efforts pushed the flies south little-by-little. |

the early 1980s. Since 1984, only isolated, imported cases have popped up, but otherwise North America has been pretty much screwworm-free. The 1990s saw continued efforts to push naturally-occurring screwworm populations south. Eventually, we got them eradicated as far south as Panama. You can read more details about this fascinating story here if you are interested.

Current Concerns

Which brings us up to current events. Over the last few months, we have seen new reports about cases of primary screwworm that have popped up along the Florida keys. Deer have been found to harbor these parasites, which were spreading quickly. With concern that the flies would make the jump to the mainland, eradication strategies were rapidly deployed on the islands. My entomologist friends and I have been tracking these stories in the news hoping to hear that the mainland was safe, but this week our fears were confirmed with the announcement of a stray dog having been found harboring C. hominivorax. The case spurred federal and state agencies to action and they are currently surveying the area to assess the extent of active screwworms in Florida.

For those worried, the stray dog was treated and is doing fine now that he isn't being eaten alive.

Aside from the obvious health concerns for people, wildlife, pets, and livestock, these flies could have catastrophic effects economically. Estimates from the USDA have reported that screwworm eradication has saved the U.S. livestock industry over $900 million dollars per year. Remember that this estimate doesn't include costs to pet-owners, breeders, or wildlife conservation efforts.

Here's to hoping that we can control whatever is already here and prevent future outbreaks, especially as if we see a long, warm spring/summer that would lead to a boom in any existing screwworm populations.

The Moral of the Story

The battle between us and the North American screwworm has been long and hard-fought. Countless man hours and dollars have gone into ensuring our victory over these winged beasties, and yet still they pop up from time to time because one person or another brought in an infected cow or doggy without considering the ramifications (or simply out of ignorance). This reinforces the importance of public outreach and extension efforts. Funding programs to continue educating the public about primary screwworms is both essential and inexpensive relative to the costs of dealing with established screwworm populations on a larger scale as was necessary in the past. Similarly, we need to be supportive of research in the control and prevention of parasitic insects.

|

| Bumper sticker from 1977. |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)