The New World, on the other hand, had a much better control of their parasites. Though there were still sanitation issues and odd behavioral practices that increase changes of parasitism, such as the intentional ingestion of arthropods that may have carried parasitic disease, Native Americans had far less severe cases of parasitism.

The most recent hypotheses for this stark contrast in New World and Old World parasitism involve the differences in medical technologies of these two groups that are...let's be honest....worlds apart. It seems that religion had a HUGE influence on how people in both regions viewed medical "science". The medical practices that spawned from these beliefs were very, very different.

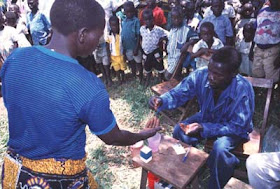

Let us first look at the New World. Many Native American cultured relied on the use of medicinal plant to cure ailments, including those induced by parasites. Though not all folk medicine has been shown to have true biological capability to cure diseases, many (if not most) of these treatment methods have been scientifically proven to actually work for controlling parasites. There are a variety of plants that have antihelminthic properties, a fact that medicine men where aware of long before the creation of microscopes and ivermectin.

Religion was important to these people, but much of the religious beliefs were centered around observations and interpretations of the natural world. Medicine was therefore developed from the things provided naturally by the gods. This notion helped them to control parasites effectively using natural botanical treatments. Many of these people were also nomadic, and those that did establish permenant homes did not live in densely overpopulated regions (at least not relative to Western Europe). This helped to control crowd parasites. Don't let this mislead you, there are many types of parasites that have been found from these people...pinworms were especially prevalent in many areas and hookworms are often found in North American coprolites. That being said, the extent of parasitism in these areas was no where near what is found in the Old World.

Religion was important to these people, but much of the religious beliefs were centered around observations and interpretations of the natural world. Medicine was therefore developed from the things provided naturally by the gods. This notion helped them to control parasites effectively using natural botanical treatments. Many of these people were also nomadic, and those that did establish permenant homes did not live in densely overpopulated regions (at least not relative to Western Europe). This helped to control crowd parasites. Don't let this mislead you, there are many types of parasites that have been found from these people...pinworms were especially prevalent in many areas and hookworms are often found in North American coprolites. That being said, the extent of parasitism in these areas was no where near what is found in the Old World.Now let's shift our focus to the Old World...specifically to Medieval Western Europe. This region of the world at this time was vastly overpopulated. Crowd diseases were ubiquitous...as you might imagine when discussing outbreaks such as boubonic plague. These people had TONS of whipworms and maw worm infections. Not only were these parasites more prevalent than those found in the New World, they were also much more devastating. These sorts of infections can cause much more serious health problems...especially if they are not properly treated.

Speaking of treatment, let's talk about Medieval medicine. As opposed to the Native American use of natural botanicals which had antihelmenthic properties, Medieval European physicians used treatments that rarely actually treated parasitic diseases. In fact, many of the practices of these doctors exacerbated the problems their patients were dealing with. Scienfic studies of medicine were non-existant. Medicine during this period was regulated by spiritual influences and religious beliefs. As Christianity began to push out paganism, so did prayers begin to push out the use of herbal remedies. The idea in those days was that people became ill when they angered God and were in need of punishment or when they were being targeted by demons. Repentance of sins and exocism were the most important vehicles to medical recovery. Much of society actually saw medicine as a profession unsuitable for Christian people since disease was mandated by God. Despite this notion, some monastic orders, such as the Benedictines, were known for their involvement in caring for the sick and dying.

Speaking of treatment, let's talk about Medieval medicine. As opposed to the Native American use of natural botanicals which had antihelmenthic properties, Medieval European physicians used treatments that rarely actually treated parasitic diseases. In fact, many of the practices of these doctors exacerbated the problems their patients were dealing with. Scienfic studies of medicine were non-existant. Medicine during this period was regulated by spiritual influences and religious beliefs. As Christianity began to push out paganism, so did prayers begin to push out the use of herbal remedies. The idea in those days was that people became ill when they angered God and were in need of punishment or when they were being targeted by demons. Repentance of sins and exocism were the most important vehicles to medical recovery. Much of society actually saw medicine as a profession unsuitable for Christian people since disease was mandated by God. Despite this notion, some monastic orders, such as the Benedictines, were known for their involvement in caring for the sick and dying.By the time of the 12th century Renaissance, medicine had greatly improved as medical texts became available following translation from Greek and Arabic. Prior to these texts, classical medicine was largely influcenced by the works of Hippocrates and Galen. The writings of Galen were based on animal dissections...which gave false assumptions about human anatomy. His work also discouraged physiological research by incorrectly describing the process of circulation.

The major medical theories were typically fusions of classicaly held ideas, pre-Christian beliefs, and Christian beliefs. Techniques for diagnosis and treatments are reflective of such fusions. The most underlying principle of medicine was the belief of the humours. This was the belief that the body has four humours (fluids) made by the body that must maintain a balance to keep a person healthy. If any of these humours became unbalanced, a person became sick. Treatments were aimed at restoring balance to blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Treatments involved changes in diets, administering medicines, and using leeches for blood-letting. The humours were also associated with the seasons (blood-spring; phlegm-winter; black bile-autumn; yellow bile-summer). This brought astrology into medical practices, assigning patients to particular seasons describing their "nature" and their elements (Fire, Water, Earth, and Air).

The major medical theories were typically fusions of classicaly held ideas, pre-Christian beliefs, and Christian beliefs. Techniques for diagnosis and treatments are reflective of such fusions. The most underlying principle of medicine was the belief of the humours. This was the belief that the body has four humours (fluids) made by the body that must maintain a balance to keep a person healthy. If any of these humours became unbalanced, a person became sick. Treatments were aimed at restoring balance to blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Treatments involved changes in diets, administering medicines, and using leeches for blood-letting. The humours were also associated with the seasons (blood-spring; phlegm-winter; black bile-autumn; yellow bile-summer). This brought astrology into medical practices, assigning patients to particular seasons describing their "nature" and their elements (Fire, Water, Earth, and Air). The use of herbal remedies were influcenced by pre-Christian religious beliefs, but the success of such remedies were judged by their ability to rebalance the humours. Such remedies were also influenced by the Doctrine of Signatures...a book connecting medically important plants to disease treatment not by their ability to cure diseases, but by their morphological likeness to various body organs. For example, liverworts were thought to be useful for treating liver problems since they had morphological similaries to the shape of the liver. These beliefs stemmed from the idea that God left signatures or mark on these plants as clues to how he intended for people to use them. Much like the writings of Galen, this text slowed the progress of true medical science.

The use of herbal remedies were influcenced by pre-Christian religious beliefs, but the success of such remedies were judged by their ability to rebalance the humours. Such remedies were also influenced by the Doctrine of Signatures...a book connecting medically important plants to disease treatment not by their ability to cure diseases, but by their morphological likeness to various body organs. For example, liverworts were thought to be useful for treating liver problems since they had morphological similaries to the shape of the liver. These beliefs stemmed from the idea that God left signatures or mark on these plants as clues to how he intended for people to use them. Much like the writings of Galen, this text slowed the progress of true medical science. Although medicine did eventually become more relient on observations than on long-standing religious beliefs, it was a long, drawn out process that I won't got into for this blog. Suffice it to say that the majority of conventional medical practices did not actually treat people infected with parasitic diseases. Also keep in mind that some of these practices, such as blood-letting, were actually causing more harm to patients with parasitic diseases than they were helping them. It doesn't take a genius born in today's world to understand that blood-letting probably isn't the best way to treat a person with parasite-induced anemia or malnutrition/malabsorption. But in those days, that was the best way to restore balance to the humours of a person caring so many whipworms that her intestines were losing their elasticity.

Although medicine did eventually become more relient on observations than on long-standing religious beliefs, it was a long, drawn out process that I won't got into for this blog. Suffice it to say that the majority of conventional medical practices did not actually treat people infected with parasitic diseases. Also keep in mind that some of these practices, such as blood-letting, were actually causing more harm to patients with parasitic diseases than they were helping them. It doesn't take a genius born in today's world to understand that blood-letting probably isn't the best way to treat a person with parasite-induced anemia or malnutrition/malabsorption. But in those days, that was the best way to restore balance to the humours of a person caring so many whipworms that her intestines were losing their elasticity. Moral of the Story

It is easy to look back now and see the flaws of medical history, but can we apply the lessons learned from those mistakes to our culture today? Is spirituality important? Absolutely! But given a choice between praying for a migrane to go away and taking an asprin...I'd take the asprin (and probably pray too because it couldn't hurt...but I wouldn't rely solely on the prayer...that's just silly!). I doubt God wants any of us to get sick or die, but the world around us is full of infectious agents and eventually we will do both. If you believe that God gave us the free will and the intellegence to develop medical technologies that prolong our life, then you have to agree that using those technologies is not somthing that goes against God's will. Most Christians aren't this stupid (I hope), but there are certainly those who feel that they shouldn't trust medical science and that leaving it all up to chance is a superior option.

That little rant aside, we have archeological evidence to prove that people in the New World had more efficent ways of controling their parasite burdens. Everything from the way these people lived, to the way they treated their sick was superior for keeping parasitic infections at bay. The people of the Old World were much less effective because of overcrowding and flawed medical practices influenced by religion. It is amazing to think of these parasite-ridden Europeans as the very people who would later see the Native Americans as "savages".